Manga Dreaming

The ‘irresponsible images’ of cyberpunk in Japanese Animation and Comics

Norris, C. (1996). Manga Dreaming: The ‘irresponsible images’ of cyberpunk in Japanese Animation and Comics. Honours Thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide.

2025 note: This thesis was originally submitted in December 1995 for my Communication Studies honours program (awarded in 1996). In 2025 I have made simple edits to improve grammar, expression, and comprehension while preserving the original content and insights. These updates aim to enhance readability and ensure the work remains accessible to a broader audience. No changes have been made to the arguments or research as they were presented in 1996.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Part 1: Blueprints on the Destruction of the World

- 1.1 What is Anime and Manga?

- 1.2 Animating the World’s Worst Nightmare

- 1.3 The Guilty Text

- 1.4 Sanctified Misunderstanding

- 1.5 The Early History of Japanese Manga and Anime

- 1.6 The Dance and Dream of Images

- 1.7 ‘Manga as Air’

- Part 2: ‘Manga’s Take on Contemporary Identity’

- 2.1 Electro Blood

- 2.2 Heart Core

- 2.3 Ultimate Questions

- 2.4 ‘More Human than Human’

- 2.5 Cultural Differences

- 2.6 Religious High-Tech

- 2.7 ‘Time to Die’

- 2.8 Ghost in the Shell

- 2.9 Disconnect

- Conclusion: Cyborg Language

- Appendices

- References

Abstract

Japanese anime (animation) and manga (comics) challenge prevailing Western ideas of what animation should be (Leonard, 1995; McCarthy, 1993; Staros, 1995; Yang, 1992; Haden-Guest, 1995). They engage Western viewers/readers in a way that alters perceptions of identification and subjectivity, disrupting the comfort and stability of an identity rooted in concepts of ‘humanity’. These ‘assaults’ often occur during violent and sexual scenes, which is the focus of my study. I have specifically selected the cyberpunk genre within anime and manga to explore the potential pathways offered within these violent and provocative texts.

Two examples of early anime guide books for Western audiences, Helen McCarthy’s (1993) Anime! – A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Animation and Albert Wong’s (1995) Anime Reference Guide: Anime eXpo 95.

This is a study about the politics of the human body, the construction of masculinity and femininity, and the ruptures created by the cyborg body (Haraway, 1991; Springer, 1991; Neal, 1989; Pyle 1993) – with its aesthetics of masochism, violence and eroticism. Influenced by Queer and Feminist theory, it is also a study about the politics of difference and origins (Kristeva, 1980 & 1984; Helen (Charles), 1993; Williams, 1990) which have been projected onto the cyborg body, a difference which is situated between human and non-human, male and female, organic and machine, and displays the tenuous and porous nature of these categories. My study asks whether the cyborg serves as a motif of radical liberatory freedom (Haraway, 1991) or whether its subversive characteristics have been co-opted to serve patriarchy and reinforce traditional masculine and feminine ideals of ‘normality’ (Springer, 1991; Jackson, 1981). It incorporates postmodern theory (Bishop, 1992; Brophy, 1995; Docker, 1994; Ross, 1989); literary theory (Jackson, 1981; Kristeva, 1980 & 1984); animation theory (Cholodenko, 1991; Kaboom, 1994; The Life of Illusion Conference, 1995) and current screen theory (Pyle, 1993; Shaviro, 1993; Studlar, 1985).

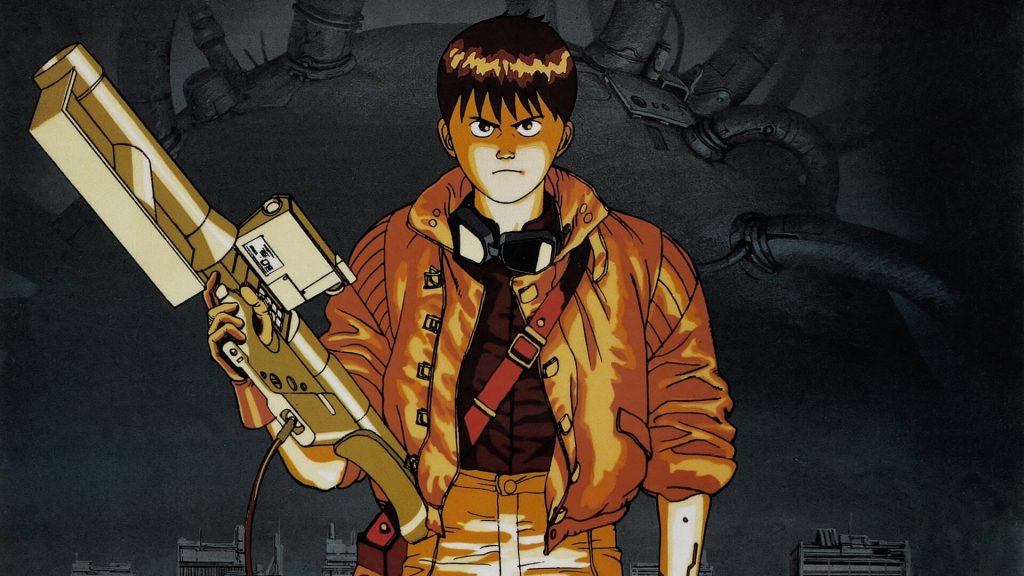

This thesis is divided into two sections. The first part problematises my approach to a familiar text, yet one that is very different due to its Japanese origins. I map the previous research and strategies within this field in academic and fan communities, and then detail a brief history of anime and manga, from its origins in Japan to its appropriation by the West. I do this primarily to contextualise manga and anime and avoid characterising these media as ideologically innocent texts that occurred overnight, heralded by the anime Akira (Otomo, 1988).

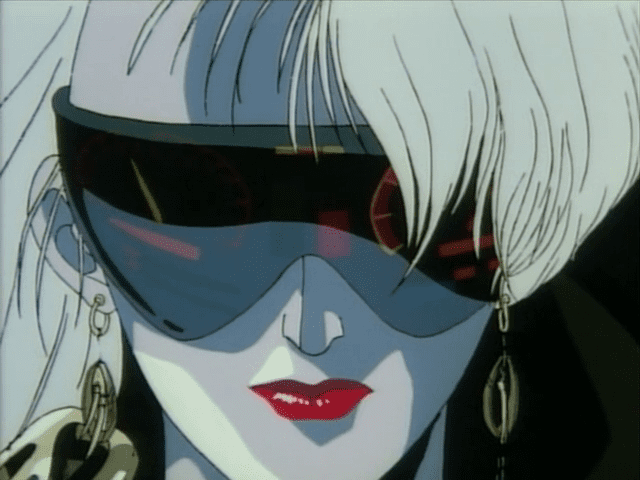

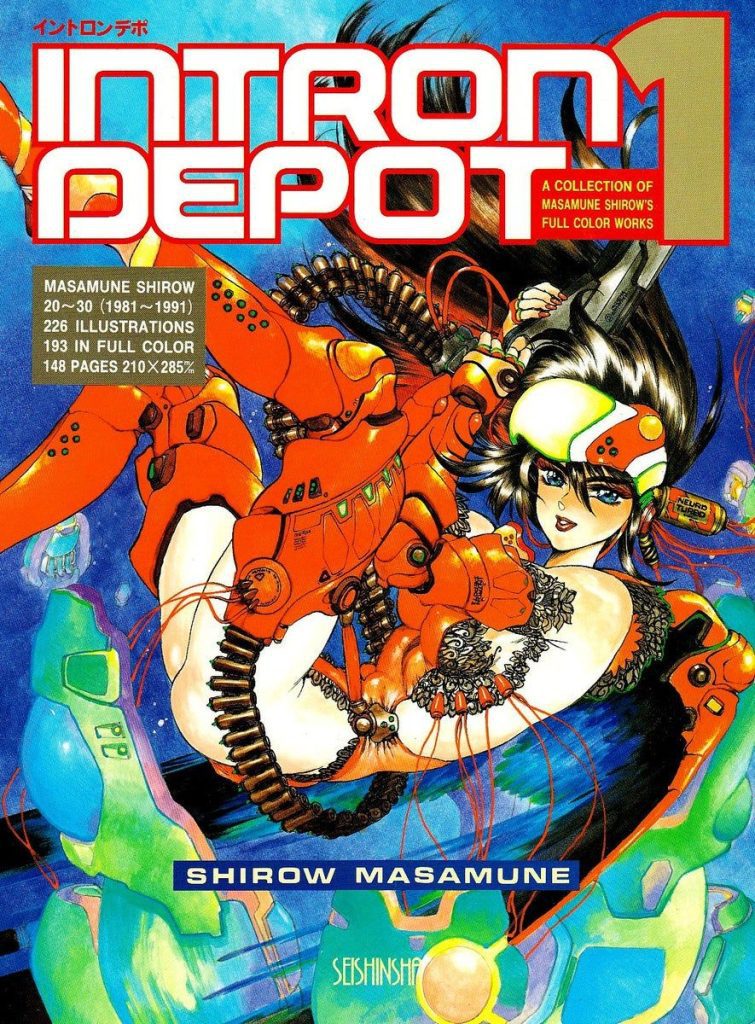

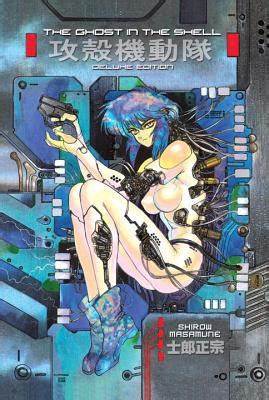

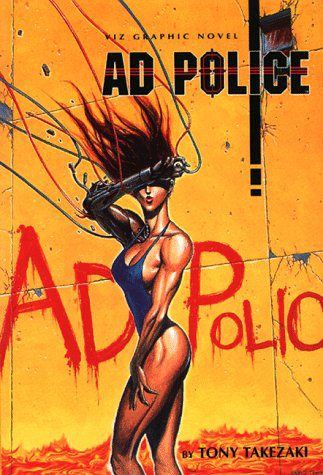

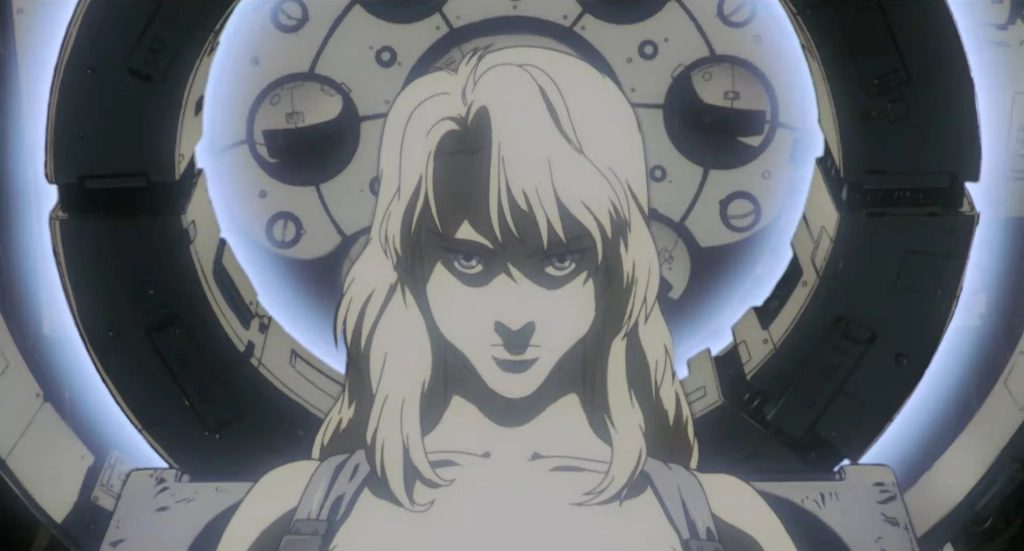

The second part discusses the cyberpunk genre within anime and manga. This is a violent and provocative study in which I aim to disrupt and problematise issues of the body as they relate to the cyborg identity and expose both the conservative and subversive tensions operating within this genre. It is a mapping of sexual bodies, violent machines and fragmented notions of personal identity, gender and humanity, which have been strewn over the postmodern landscape of these cyberpunk texts. To this end, I shall analyse the manga Ghost in the Shell (Shirow, 1989) and anime AD Police Files (Ikegami & Nishimori, 1990), as well as their grim depiction of a cyberpunk future intricately intertwined with contemporary fears over technology, gender, and sexuality.

The cyborg body of the anime and manga text and image demands new ways of engagement by academics. This thesis attempts to chart some of the possible ‘cross-over’ points which are driving a dramatic and far-reaching paradigm shift (Shaviro, 1993) – to articulate alternative conceptualisations of pleasure and resistance which exist with reactionary and conservative strains.

Introduction

The circuitry of the machine suddenly reaches a point where red corpuscles swarm in a hazy mist of visceral intimacy. So, with deliberate action, the body becomes vulnerable to an intense, uncertain, and ambiguous struggle towards an end as open and multiple as the forms that attack it. The tension and anxiety of the body bleed into the boundaries of identity, gender, and perception, heralded by the sound of the action-violence-sexual dynamics of the twin themes of the destruction and apocalypse of the hentai (pervert) and the freedom and liberation of the kawaii (cute). But who controls and commands these images?

The body is merging with the machine, and my reaction is one of wanting to belong to this technology while at the same time scrambling away from the consumption of flesh and chrome in a frenzy of visceral confusion. I am seduced, not coerced, by the image of the cyborg body; I want to be a part of it.

The anime cyborg offers a seductive portrayal, providing an intimate understanding of many of the dilemmas characteristic of postmodernism, expressed through the images of Japanese anime and manga. It is about how I relate to the images produced by the animated apparatus of anime, as well as the drawn pictures in manga. It is a study flirting with concepts of postmodernism, the politics of the body, the construction of identity, and the aesthetics of masochism.

My approach here follows Steven Shaviro’s (1993) The Cinematic Body, where he attempts to explore similar concepts about cinema, specifically looking at the works of David Cronenberg, Andy Warhol, George Romero, Fassbinder, and, somewhat surprisingly, Jerry Lewis. I will explore the way the cyberpunk genre in manga and anime uses pornography, violence, and religion for its ends and the portrayal of the futuristic landscapes of the apocalypse and cyberspace and the effects they have on notions of the self and machine, the body and ‘consciousness’. There is a demand for new and different ways for academics to relate to the ‘fantastic’ text. I apply the term ‘fantastic’ in the same manner Rosemary Jackson (1981) does in Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, where she paraphrases Bakhtin:

“He (Bakhtin) points towards fantasy’s hostility to static, discrete units, its juxtaposition of incompatible elements and its resistance to fixity. Spatial, temporal, and philosophical ordering systems all dissolve; unified notions of character are broken; language and syntax become incoherent. Through its ‘misrule’, it permits ‘ultimate questions’ about social order or metaphysical riddles as to life’s purpose. … It tells of descents into underworlds of brothels, prisons, orgies, graves; it has no fear of the criminal, erotic, mad, or dead” (p. 151).

To engage with the issues of this text: new formulations and depictions of the human body, new technologies and the dynamics these are creating around notions of fantasy and reality, and the relationship that significant sub-cultural groups like fans (otaku in the case of anime and manga) are establishing between themselves and the text. My aim is not to establish what the ‘right’ answers are to these questions, nor to compel acceptance with the understandings I arrive at, but to convey a sense of the excitement surrounding anime and manga for a Western fan. To describe the intensity of the ambiguity, confusion, and intolerable ‘openness’ that characterises my relationship with these texts and, at the same time, to provoke a questioning and engaging stance requires a diverse yet considered approach.

This thesis seeks to challenge the numerous ‘truths’ of ‘academic authority’, particularly the ‘explaining’ and ‘telling’ of texts rooted in fantasy, such as the cyberpunk texts I am examining. Rather than ‘explaining and telling,’ I propose instead an ‘understanding’ that seeks to express the incommunicability of an image shrouded in silence and shadow — the novelty of Japaneseness from an Anglo-Australian perspective. The texts I will be studying are two of the more intense and grim cyberpunk texts available at the moment: Masamune Shirow’s (1989) manga Ghost in the Shell and the anime OVA AD Police Files (Ikegami & Nishimori, 1990).

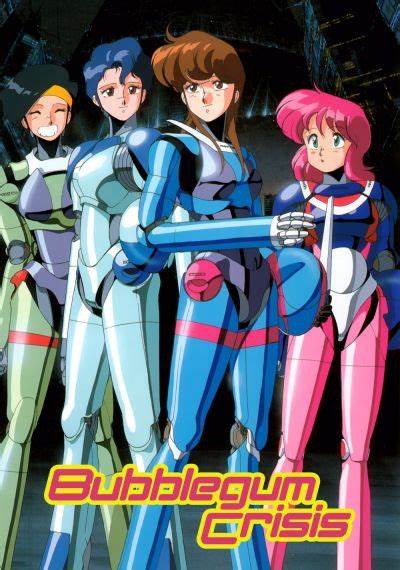

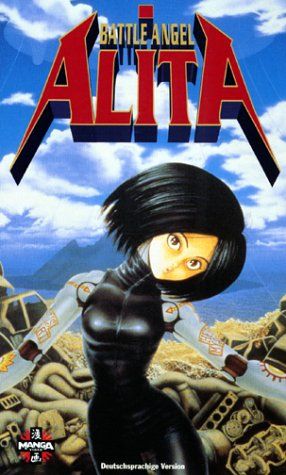

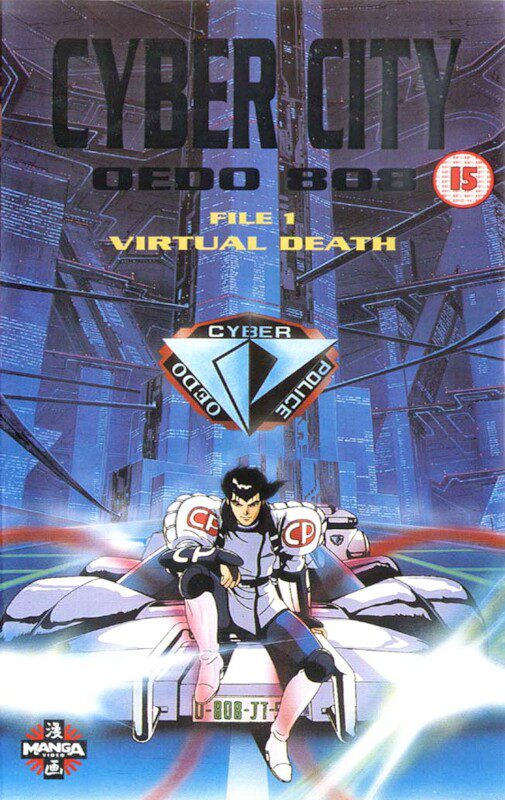

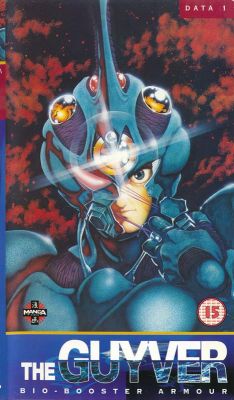

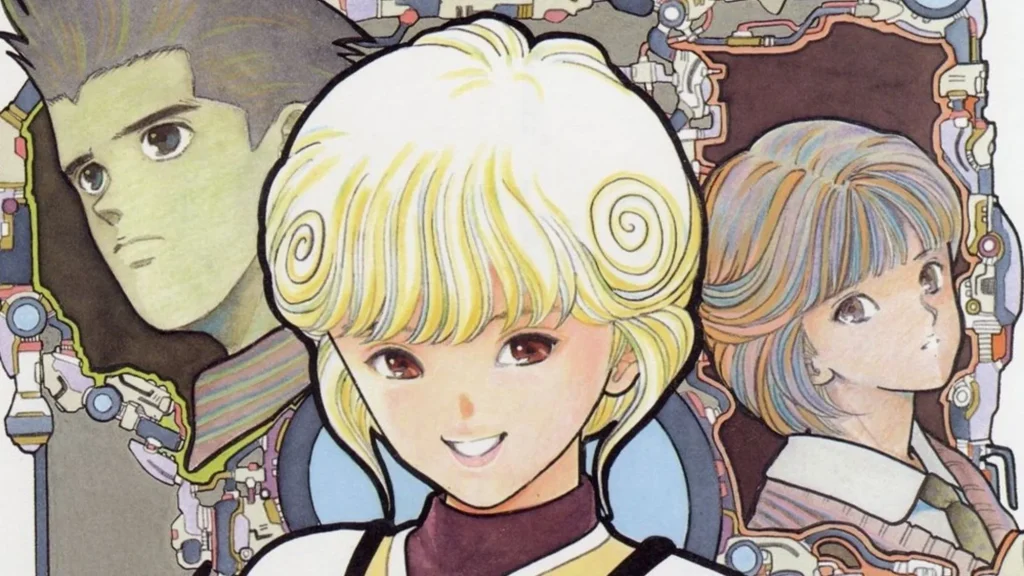

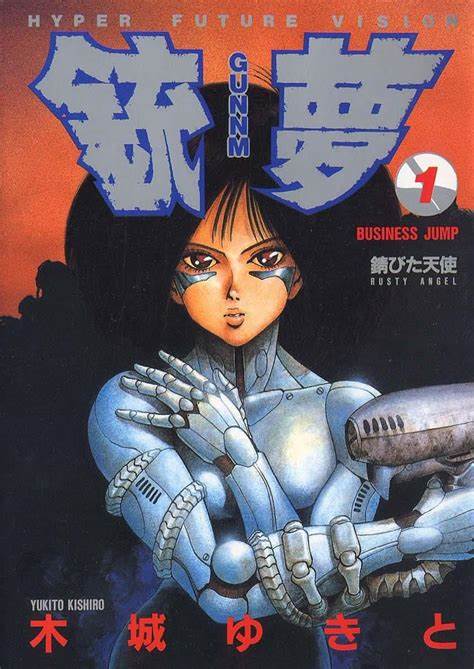

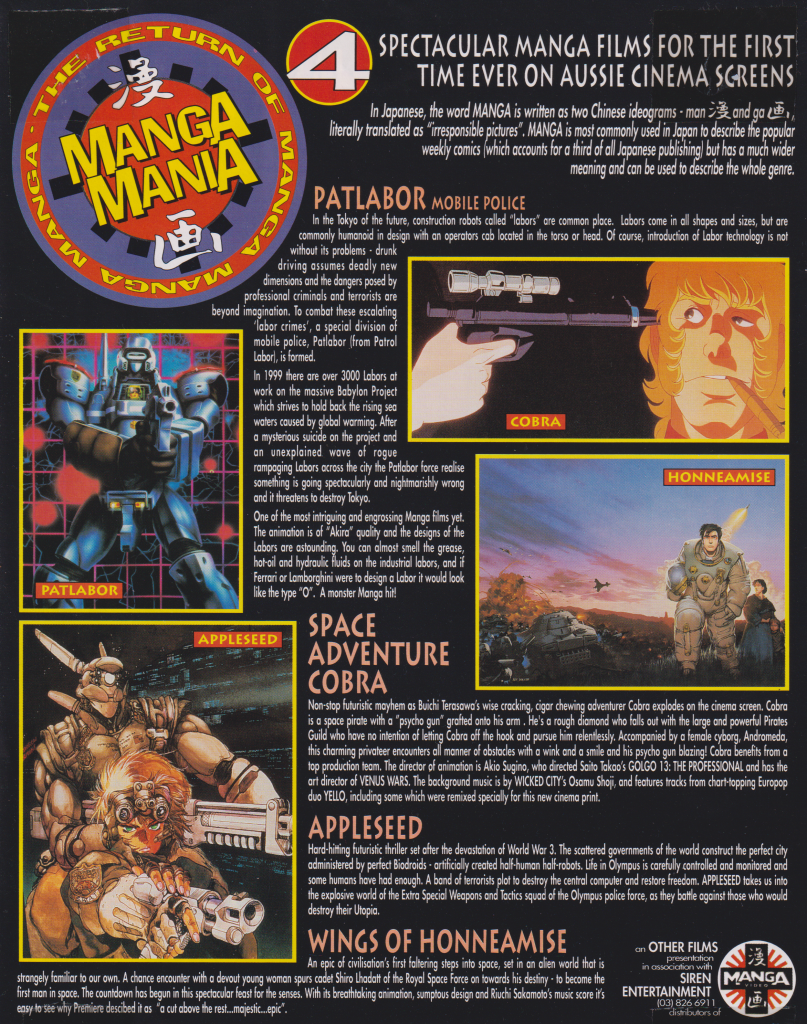

These are amongst the small but growing titles in a rapidly expanding field of cyberpunk anime today. Other Japanese cyberpunk titles that I base my ideas on include Battle Angel Alita (Fukutomi, 1993), The Guyver (Tsuchiya, 1989), Cyber City Oedo 808 (Aikawa, 1990), Geno Cyber (Koichi, 1994), Armitage III (Kudou, 1995), Patlabor (Oshii, 1989), Bubblegum Crisis (Hirameki, 1987), Appleseed (Kudou, 1988), and Akira (Otomo, 1988). I employ a postmodern, cross-disciplinary approach to the texts, deliberately cultivating incongruity, difference, and disunion within my thesis to capture and ‘flesh out’ the violence and ‘beyond academic-objectivity’ seduction I observe occurring within anime and manga cyberpunk.

I wish to articulate the strange realm of fascination that captivates me in the anime and manga images. I aim to explore the highly charged space that the anime scene or manga panel creates with its aesthetics of violence and sexuality, which impact upon me in a disturbingly direct and heterogeneous way that dissolves any notions of fixed identity.

Can I capture the “excruciating unresolvable ambivalence” (Shaviro, S., p. ix) that characterises the gender-bending, identity-collapsing, viscerally charged strategies of anime and manga cyberpunk? Are they creating a new archetype or rendering a highly charged space onto which contemporary fears are projected and the future possible death of outdated traditions of oppression is enacted? What new ‘language’ is anime and manga cyberpunk provoking us to recognise?

Part 1: Blueprints on the Destruction of the World

1.1 What is Anime and Manga?

What sets anime and manga apart are their unique narratives. A mysterious force can transform a teenager into a devil creature of immense power, who then graphically slaughters a massing legion of evil spirits and monsters attempting to invade human reality. A young girl is found in a junkyard, rebuilt by a kindly doctor and begins her journey to discover her identity and soul in a dangerous and deadly environment. A cyborg attains consciousness and attempts to create a new world order of perfection, thereby allowing its rule over the inadequate humanity. A high school student’s gender shifts when they come into contact with hot or cold water. Unknown forces torture and consume people, grant them immense powers and transform them into monsters, cyborgs, animals, ghosts, anything.

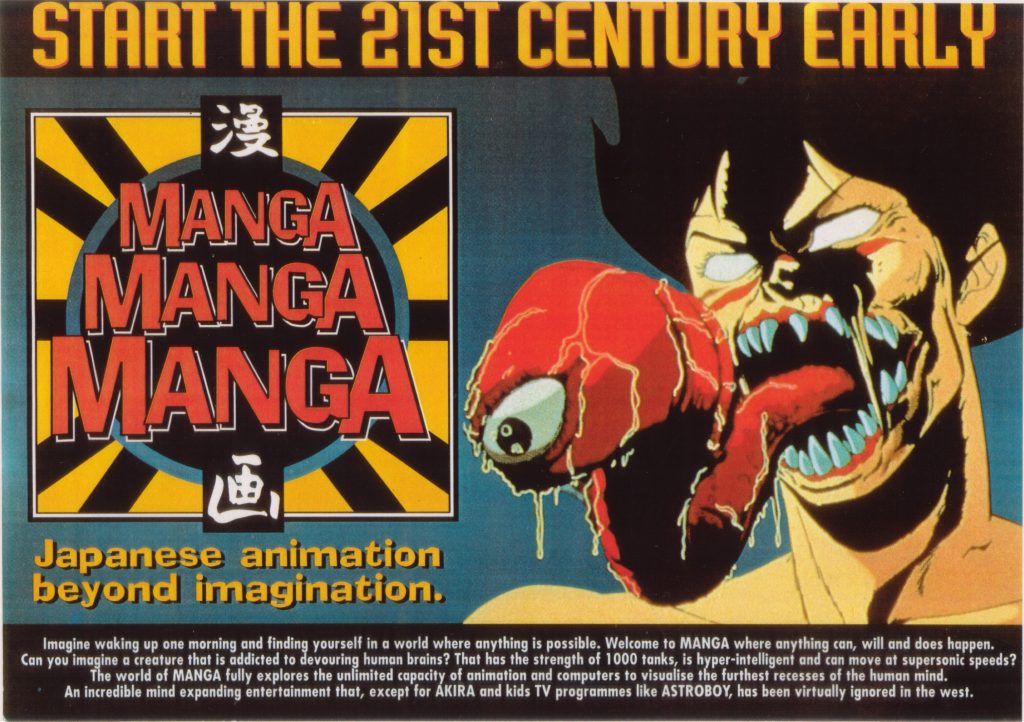

The stories above represent a small fraction of the vast Japanese phenomenon known as manga (literally translated as ‘irresponsible images’) and anime (the Japanese word for animation). These two media are more than comic books and animation as we have known them in Australia. They have been a crucial part of Japanese culture since at least the end of World War Two, yet have, until recently, received only scant attention from the Western media. However, recently, around Australia, Japanese animation and comics have slowly been developing a small but growing fan base in comic book stores, fan clubs, and on various commercial and social Internet sites. Thanks to a growing marketing drive from American and British companies, they are rapidly becoming a mainstream part of the Australian cultural scene.

So recent is this appropriation of forms that discussion of anime and manga in popular Western magazines (both fan and academic publications) reveals an interesting, if not entirely productive, attempt to understand and explain this strange new form. On the theoretical side, there is an unfortunate and sizeable lack of diverse and rigorous inquiry. Most articles and publications focused on Japanese animation and popular culture that are available to English-speaking audiences are, unsurprisingly, written by Westerners for Western readers. While they may include translated works by Japanese authors, these are often targeted at a largely uninformed or confused Western audience. There is a significant shortage of translated writings from Japanese authors in this field for those wishing to go deeper.

More earnest and public dialogue has been established online between Western and Eastern fans of this genre. Online groups, such as rec.arts.anime and rec.arts.manga, on the newsgroup listing and individual subscriber addresses, like that for the translation project of Video Girl Ai (1992), display the importance of the internet for this genre. It is a significant emerging area that is often overlooked in discussions of anime and manga.

The phenomenon of fan culture on the internet and in clubs and societies is diverse and dynamic. For instance, one strong group within the anima and manga ‘community’ comprises what could loosely be labelled ‘purists’: those who believe dubbing English or American voices over anime is blasphemy and that no alteration should be made to the original Japanese work apart from subtitling. These purists have formed a stable and powerful force in maintaining a recognised subculture centred on Japanese pop culture, specifically manga and anime, influencing the growing merchandising and appropriation of anime in the West and serving as an important source of information.

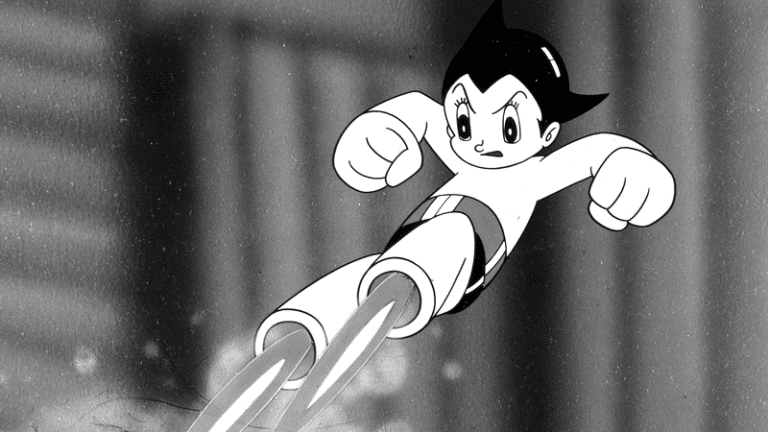

Fan subcultures play a crucial role in circulating and localising anime and manga. There is growing academic interest in how these communities appropriate and shape manga and anime to fit their local contexts. For instance, Andrew Leonard’s (1995) article, “Heads Up, Mickey,” in Wired, and Philip Brophy’s (1995) “Osamu Tezuka: Glimpses of a Fantastic World” in Film News raises interesting questions. Brophy, for example, explores why many Westerners mistakenly believe that the popular anime series Astro Boy was produced in the United States when, in fact, it was made in Japan. Brophy (1995) suggests that

“how readily an American dialogue track can cast any production in the shadow of its accent” may contribute to this misconception (p. 7).

For further exploration, consider Chapter 8, “Anime in Britain,” from Helen McCarthy’s (1993) book Anime! A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese Animation, as well as Jeff Yang’s (1992) article “Anime Rising”. Other helpful works include Adams and Hill Jr.’s (1991) article “Protest and Rebellion: Fantasy Themes in Japanese Comics” and Kinko Ito’s (1994) sociological paper “Images of Women in Weekly Male Comic Magazines in Japan”.

As is well established by academic theory, texts are not ideologically neutral. Animated films like Akira did not emerge in a vacuum; they are products of a culture that possesses distinct and unique aesthetic values, as well as specific methods of creating images and narratives. To reference Walter Benjamin (1973), they are shaped by the production processes of their time. A considerable amount of literature has explored the visual aspects of Japanese culture and the impact that a ‘comic-obsessed culture’ like Japan’s can have on perception and consciousness.

Annette Roman (1995), the editor of Manga Vizion, a recent manga anthology published in the United States, asks:

Want to know why manga take up nearly a third of all Japanese publishing? Why Japan uses more wood pulp for manga than it does toilet paper? Why one Japanese neurophsyiologist speculated that the nonlinear logic used to read words and pictures together could be a factor in Japan’s affinity for computers … and why Mitsubishi engineers claimed their favourite manga helped them produce better plastics? (I did not make this up!) (p. 2)

The editor pleads, “I did not make this up!” in a tongue-in-cheek jibe. With these words, the editor presents the unbelievable strangeness of anime and manga to a foreigner. Anime and manga captivate Western audiences with their distinctive graphic and textual style, which thrives on what is not present. To a first-time reader or viewer, meaning may occur through evocation and suggestion rather than through explicit revelations. For the new fan, watching anime or reading manga becomes an experience of grasping words and images while constantly yearning for something more beyond them. It’s an act of actively theorising and guessing what the image represents and diving deeper into the layers of meaning it holds.

The lack of a guidebook and this yearning for something more reflects the experience of suddenly discovering Japanese animation and comic books. There’s an awareness that a rich history lies behind it, but accessing that history is elusive. While some references resonate and the basic shapes and stories seem familiar, much remains different and strange. These anime and manga are not like the cartoons typically shown on Saturday mornings; they can be adult, violent, and are not intended for children.

As Peter Bishop (1992) says, “(images) are not the same as “optical pictures, even if they operate like pictures … We do not literally see images or hear metaphors; we perform an operation of insight which is a seeing-through or hearing into” (p. 13).

In this context, a ‘Westerner’ with no prior experience of the Japanese ‘condition’ or language often constructs meaning and appropriates images and text for personal purposes and desires. Readers feel that they are never ‘provided with a definitive statement like, “This is the meaning of the manga.” Instead, as will be developed in Part 2 of this thesis, understanding manga and anime from a Western, Anglo-Australian perspective involves ‘exploring the desires, resistance, and pathways presented by anime and manga for this audience. This exploration reveals the diverse and dynamic qualities that manga and anime offer, which can reshape our ideas of identity and subjectivity. As Peter Bishop (1992, p. 18) suggests:

To denaturalise images is not to unmask them, but to don death masks ourselves and to join in the dance and dream of images; to see ourselves as an image among images. The task is therefore not to reveal the hidden, but to follow the trace of the visible to where it seems to become invisible.

However, some academic writing (see Adams & Hill 1991; Ito 1994; Ledden, Sean & Fejes 1987) on manga still relies on the totalising discourse of psychoanalytic theory, drawing mainly upon Freudian theory with its gender theories with scant attention to issues of transgressed gender shifts or subversions of the body through technology. Articles as Adams & Lester Hill Jr.’s (1991) Protest and Rebellion: Fantasy Themes in Japanese Comics, Kinko Ito’s (1994) Images of Women in Weekly Male Comic Magazines in Japan, and Sean Ledden & Fred Fejes’s (1987) Female Gender Role Patterns in Japanese Comic Magazines mainly dwell on depictions of women and the oppressive and totalising ‘male’ gaze, trapping any possibility of radical or subversive potential within the closed boundaries of male/female binaries and patriarchal oppressiveness. Such positions overshadow the playfulness that often occurs within the text (see my discussion of this in part 2) and come at the expense of a more inclusive and open-ended understanding that emphasises issues of access, freedom and playfulness rather than command, control and information.

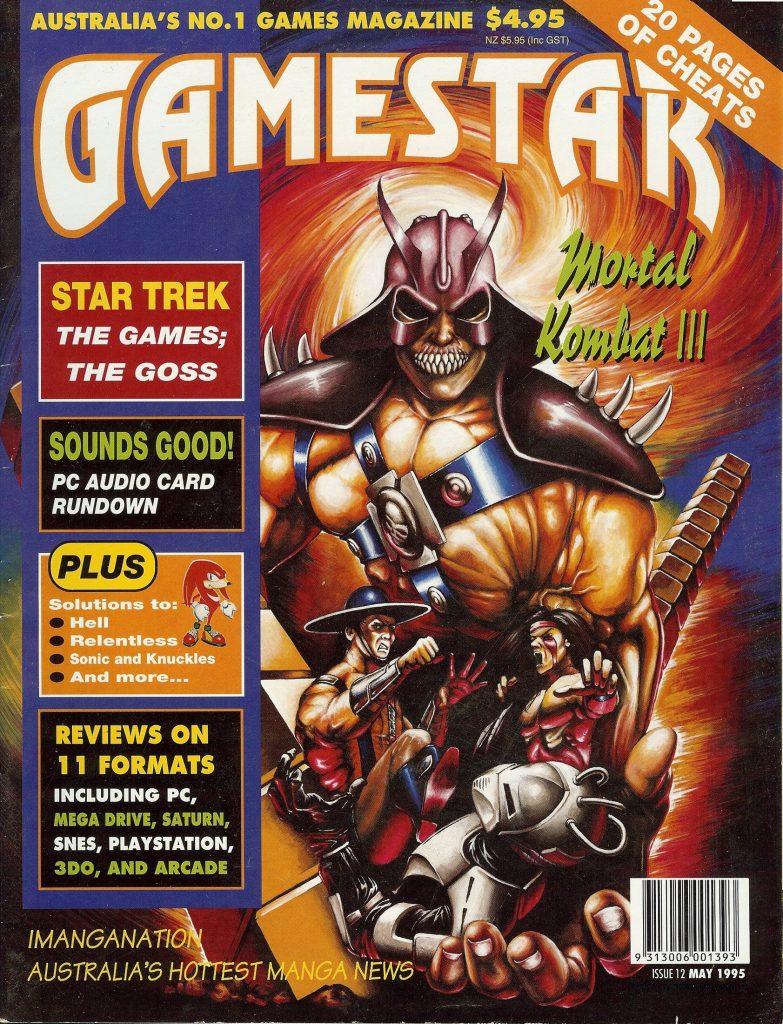

Fan discourse and fan communities are rich with themes of access, freedom, and playfulness, many of which remain under-theorised. Fans regularly contribute articles to popular computer and arcade game magazines. For instance, Janice Tong writes articles for Gamestar, an Australian computer gaming magazine published by ACP Publisher in Sydney. Other notable publications include the British magazine Super Play, dedicated to the Super Nintendo.

Showing the emerging popularity of anime and manga style and content in Gamestar 12 (May 1995) and Super Play Issue 31 (May 1995).

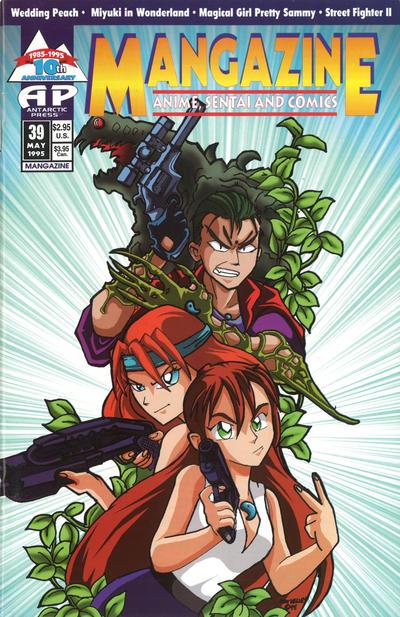

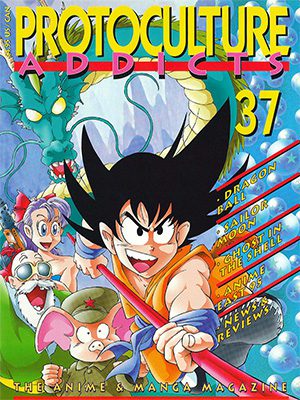

There was also some cross-over in demographics between tabletop role-playing games and manga and anime as seen in White Wolf mainly known for its games like Vampire: The Masquerade and its publishing arm that distributed the Canadian based anime and manag magazine Protoculture Addicts. Additionally, there are magazines entirely devoted to anime and manga. In Australia, two commercial fanzines are produced by major distributors of anime: Mangazine, published by British Manga Entertainment, and Kiseki Fanzine, released by Kiseki Films.

Mangazine #39 (1995) and Protoculture Addicts (Nov/Dec 1995).

There are also several international publications focused specifically on manga and anime that one can find in some specialty comic book stores in Australia, including Animage, published by Tokuma Shoten; Animedia, published by Gakken Shoten; Animerica, issued by Viz Communications in San Francisco, USA; Anime UK, published by Anime UK Press in London, England; Anime V, published by Gakken Shonen; the Japanese-language magazine Newtype, published by Kadokawa Shoten; and Protoculture Addicts, published by Ianus Publications in Canada.

Many of these efforts aim to legitimise the significance of mature animation and comics, challenging the traditional perception in mainstream Western media that they are only for children. While there are some introductory discussions about manga and anime, in-depth analysis is scarce regarding how these foreign forms are being integrated into Western culture, including Australian culture. Additionally, there is a need to explore the opportunities created by the unique elements that anime and manga bring to the comic and animation formats, particularly emerging digital editing technologies. For instance, an interview with Buichi Terasawa in Multi-Media (1995) touches on these themes.

On a more commercial note, interactive computer role-playing games, many of which were spin-offs from anime or manga series, or even inspired some anime, such as Dragon Knight. Some discussion has occurred in this regard, such as Alan Cholodenko’s work, as well as the Illusion of Life and Life of Illusion conferences held in 1988 and 1995. The Life of Illusion conference, in particular, focused on post-World War II animation in the United States and, more importantly, Japan. The conference highlighted the need for new ways of interpreting and experiencing the complex heterogeneous possibilities of the animated form. The theoretical base used must be able to shift between the boundaries often crossed by anime and manga to examine the possibilities of the word, sound, and image, as well as the longing for more than the word, sound, and image can convey. As Alan Cholodenko (1991) says of the study of animation:

To theorise about animation implies seeking out animation itself, speaks of an order in between the multifaceted mobile sign that critical theory, high and low culture, liberal studies, film studies, psychoanalytic film study link together in an attempt to probe the very idea of animation itself and its … relation with animation style, animation theory, animation form and the televisual. To think about animation as film and as television and as an idea suggests that all are complexly intertwined with each other. (p. XX).

Although the cultural subtleties of some anime/manga may not be fully appreciated, the unique and provocative style of much of this media certainly elicits a strong reaction, for, ‘in essence, it’s not only the way characters are drawn that is unique, but the whole perception of what cartoons should or should not be.’ (Tong, Janice 1994, p.19). The issue of control and command is crucial (‘what cartoons should or should not be’). It becomes important to engage with and challenge any theory or model that attempts to restrict the diversity of a medium or applies totalising ideals to regulate and control this medium, whether this be the concerns of a right-wing Christian lobby group concerned with the effects of violent and pornographic material will have on children, or academic research searching for a causal link between violence portrayed in the media and aggressive behaviour in ‘real life’. It becomes vital in an environment that threatens to be dominated by reductive, simplistic causal models for academics to pursue pluralistic and wide-ranging research in these areas. Stuart Cunningham (1992) details the issues surrounding violence and the media as they relate to academic paradigms, community and industry interests and concerns, and policy decisions in Australia. Notably, he focuses on the importance of cultural studies to ‘articulate alternative conceptualisations of violence in accessible terms [to the general public and other interested parties]’ (p. 160). Thus, the issue of sex and violence becomes the manifestation of the tensions and sliding boundaries between text, image and viewer in the manga/anime genre. As Shaviro (1993) suggests:

In the realm of visual fascination, sex and violence have a much more intense and disturbing impact than they do in literature or any other medium; they affect the viewer in a shockingly direct way. Violent and pornographic films anchor desire and perception in the agitated and fragmented body. These “tactile convergences” are at once the formal means of expression and the thematic content of a film (p. 55)

Although Shaviro is discussing film theory in relation to specific film texts, the alternative film theory he aspires towards is well-suited to a study of manga and anime, exploring new ways of looking at the emergence of something that does not quite conform to traditional, structured approaches. I am advocating for a cross-disciplinary approach to unpack my relationship with manga and anime. This approach draws from established theories, including mythopoeic, literary, and psychoanalytic theories, while also incorporating emerging perspectives from alternative film theory, feminist theory, and queer theory. Before discussing a brief history of anime and manga, I will outline some broader debates that intersect with any attempt to theorise the imagery found in anime and manga. These debates fall into the following three sections: firstly, animating the world’s worst nightmare, which details the relationship between the fictional manga/anime text and the ‘real world’ focusing on the tenuous and constantly sliding nature of this relationship; the guilty text and sanctified misunderstandings will detail the problematic relationship which confronts my readings of anime and manga as a Western, Anglo-Australian reader. I do this to foreground the idea that, as Rosemary Jackson (1981, p. 36) suggests,

… the fantastic is a mode of writing which enters a dialogue with the “real” and incorporates that dialogue as part of its essential structure.

This ‘real’ lived experience exists both for the ‘original’ Japanese audience and the ‘appropriating’ Australian audience.

1.2 Animating the World’s Worst Nightmare

“The ego of antiquity and its consciousness of itself was different from our own, less exclusive, less sharply defined. It was, as it were, opened behind; it received much from the past and by repeating it gave it presentness again.”

(Thomas Mann, 1947)

Phillip Brophy made a revealing observation during the 1995 Life Of Illusion conference, commenting that the Japanese have a particular way of using new techniques to reveal something from the past or to give a new twist to something very old, and likewise, the inverse capacity to use old techniques to reveal something very new and different. While watching Japanese animation, one may experience a distinctly unsettling feeling that Baudrillard’s (1983) simulacra is at play, as specific images and events resonate with a historical intensity that appears to shift the context of representation. Brophy points to the example of the magical growth of a tree during the anime My Neighbour Totoro (Miyazaki, 1988), which blooms and expands in its billowing form, suggesting the distinct characteristic of a mushroom cloud from an atomic explosion. Brophy (1995a) goes on to say that ‘Events are no longer fixed and temporal as they may once have seemed, such as the use of historical images, [which] in different contexts represent something different.’

This subtle but effective challenge to the representation of power, time and reality cannot be left at the simple stage of images no longer referring to a reality that was prior to and independent of the image, as this idea becomes inadequate when the flesh itself becomes penetrated and violated by the image. A new perspective on the body emerges, reflecting our modern anxieties and our attempts to exert control over it (for a more detailed and comprehensive discussion of this idea, see my discussion of the cyborg body in Part 2).

One of the most notorious and groundbreaking anime series, Chojin Densetsu Urotsukidoji (1987), also known as Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Overfiend or The Wandering Kid, tells the story of the coming of ‘the Overfiend,’ who will unite the three worlds of humanity, demons, and spirits. It is a violent and sexually charged work that pushes the boundaries of graphic depictions of violence and horror. However, it is not just a collection of images depicting the apocalypse and demonic possession. Urotsukidoji is a dense and complex narrative that explores the personal destruction of the soul, examining its implications for human morality, religion, and philosophy. McCarthy (1993) relates this eroticism and violence to Japanese folklore and postwar trauma, highlighting how this type of horror in anime represents an aesthetic overload and symbolic disruption reflecting technological anxieties and fear of identity dissolution.

The body itself is the landscape and manifestation of violence and desire in anime. As a teenager becomes the legendary destructive Overfiend and struggles with a body in constant flux and transition from human to non-human, the significance of the body in this context becomes intense and profound. Similar motifs of bodily transgression and anthropomorphism cling to the cyborg machine/flesh, body/identity confusion of the young girl who has immense psychic powers and becomes an organic machine beast in GenoCyber (1994) or the young student who accidentally becomes infected with a parasitical element that is an alien form of advanced combat technology known as ‘bio-booster armour’ in The Guyver (1989), and the unstable cyborgs in AD-Police (1990) such as the RoboCop style character Billy. The images, especially those based in cyberspace or those depicting monstrous or mechanical penetrations within the body, point to a critical shift in the relationship between the image and the body.

Anime, such as Urotsukidoji, visually and thematically blur the boundaries between body, image and identity. As Shaviro (1993, p. 138) says: “Media images no longer refer to a real world that would be (in principle) prior to and independent of them, for they penetrate, volatize, and thereby (re)constitute the real.”

1.3 The Guilty Text

What happens when Western readers try to understand Japanese animation and comics? Manga and anime offer pleasures that go beyond mere escapism from cultural or social constraints and cannot be reduced to a historical survey of the forces driving cultural cross-fertilisation. What if the forms contained within manga and anime are resistant towards Western academic classifications of identity, empowerment, false consciousness, and critical understanding? I have chosen these particular issues because they represent the most common areas associated with ‘fantasy’ by academics. As Andrew Ross (1989, p. 193) suggests,

“To read these conventional narratives as if they directly contributed to “harmful effects” in the lived patriarchal world is not only to directly equate the work of fantasy with a notion of “false consciousness,” but also to patronise their readers as mindlessly self-destructive.”

How far am I trying to possess something that has already possessed me, a medium based on imparting life and evoking the soul, the medium of animation, and an appreciation of another culture, another place, Japan? Brophy’s suggestion of a new twist on an old idea offers the possibility of a subversive reading of dominant Western myths, ranging from identification to epistemological issues of the body, image and identity.

William Routt presented the concept of the ‘soul’ and ‘life’ of animation in his 1995 paper, De Anima, at the ‘Life of Illusion Conference’. Routt’s paper focused on the manga and anime Battle Angel Alita and traces the meaning of the word animation from “the action of imparting life, vitality, or (as the sign of life) motion” to its Latin roots of “air, breath, life, soul, mind”. As Routt suggests,

“This sense of “animation” is metaphorical, and metaphors are interesting partly because of how they preserve original sense at the same time that they make new meanings. Metaphorical usage makes almost any phrase of contemporary language a vehicle of history, representing the past inescapably in all speaking and writing. No matter how many times or in how many contexts we use “animation” to mean “cartoons”, the sense of imparting life or being alive continues to be evoked. Moreover, of course, the reverse is also true. The word confuses literal and figural meanings, presentation and representation.”

It is with similar sentiments that I also evoke the ‘life’ and ‘soul’ of animation, in this case, to display the rich history of the word’s meaning and the profound and fundamental questions of ‘life’ and the ‘soul’ that animation hints at.

Identification is one of the central issues I will discuss in greater detail in Part 2: Manga’s Take on Contemporary Identity. However, briefly, here I intend to show that anime and manga expand the possibilities for multiple identifications. Here, my definition of identification rests on a far broader interpretation than simple empathy and association. I am referring to how we weave different threads that represent a complex mixture of self and other, showing that both are related and part of the same system of a never-quite-stable identity. In the manga Ghost in the Shell, the character of Major Kusanagi must ‘cross over’ and fuse with the Artificial Intelligence entity known as The Puppeteer.

As the director of the anime, Mamoru Oshii (1995), noted, the central theme lies in the crossing over from one consciousness to another. This thesis charts the ‘cross-over’ point from West to East as I explore the possibilities and resistance provoked by the anime/manga text, highlighting the ‘excruciatingly unresolvable ambivalence’ (Shaviro, p. ix) that characterises my relationship with the text and image. Here, I am interested in the point where the reader or viewer leaves the text or walks out of the cinema and challenges the private imagination with the politics of the public, similarly the way feminism redefined notions of the ‘private’ and the ‘public’ with the idea that “the personal is the political” (Ross, p. 176). Just as Joseph Campbell poetically rallied for a call to arms by the modern hero at the end of The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), it is necessary for those researching the area of manga to challenge established institutions, models and prejudices of the community at large on behalf of the ‘gun dreaming’ Cyborg who, as Campbell has said of the heroic archetype, ‘cannot, indeed must not, wait for his (sic) community to cast off its slough of pride, fear, rationalised avarice, and sanctified misunderstanding’. Although this notion rests on a rather romantic ideal of the individual’s ability for progressive change, I believe Campbell’s infectious optimism and enthusiasm for his subject, as well as his ability to recognise the flow of change, are important aspects of this topic.

I use the term “Gun Dreaming” to capture the slightly surreal and unusual naming strategy employed in some manga titles. “Gun Dreaming” adapts the popular manga and anime series “Battle Angel Alita,” originally titled “Gunnm” (Gun Dreams) in Japanese. Those interested in this title change and the marketing strategies behind it see Fred Burke’s justification for this decision in Battling with Angelic Alita! Animerica 1.8, October 1993.

Campbell’s (1949) concept of “sanctified misunderstanding” serves as a valuable framework for examining the representations of anime and manga. It allows us to explore how and why these forms of media gained prominence while also addressing and correcting some common misconceptions. For instance, it is important to dispel the idea that the Japanese ‘stole’ the art of comics from America or that all manga, as suggested by the literal translation of the term (which means “irresponsible pictures”), are inherently pornographic, violent, and offensive forms of expression. Many in the West tend to associate this genre solely with children’s entertainment (Staros, 1995). See, for instance, Peter Hadfeld’s comment in More Strip than Comic from Punch (1988, pp. 36-37), where he writes, ‘Comics are yet another borrowed idea that the Japanese have managed to adapt and refine to their idiosyncratic tastes.’ He goes on to compare the ‘combination of lesbian sex, sado-masochism, rape, bondage, blood and violence’ (p. 37) in Japanese comics to the classic ‘archetypes’ of British comics Dan Dare and Eagle with the wholesome, youthful, clean approach to action and adventure.

1.4 Sanctified Misunderstanding

The recognition of Japan’s role in exporting its animation and, to a lesser degree, comics to the West has been, until recently, an almost unnoticeable trend. One of the reasons for this may have been cultural appropriation, which removed or localised many foreign elements of anime series, most noticeably by dubbing English dialogue over the original Japanese and removing culturally foreign peculiarities. Marketing looms as the largest guiding hand in this decision and has created a hotly disputed view of what precisely anime is. Has the decision to dub instead of subtitle irrevocably altered the artistic and cultural uniqueness of anime, or has it opened up the field to greater access for people who may never have encountered anime? One consequence of the marketing decisions in the U.S. and the U.K. has been to reduce the multifaceted nature of manga and anime, which, in Japan, stretches across every genre: science fiction, drama, comedy, detective, horror, action, historical, educational and much more; and represent it instead as a single, sensationalist genre that is easy to sell on a ‘novelty’ ticket as an ‘adult’ cartoon. As Anthony Haden-Guest (1996) writes

“Most anime that hit the export market, though, are of a specific genre. They feature superpowered humans, lethal bimbos, robots, monsters, energetic sex, explicit death, and mass annihilation” (p. 44).

The main focus of my thesis is on a genre that has been particularly effective for this marketing strategy: the cyberpunk genre. The promotion of this genre, and anime and manga more broadly, appears to centre on its adult themes of sex and violence. However, it is crucial to challenge this emerging misconception promoted by marketing practices that this represents all anime and manga. In reality, anime and manga encompass a much broader range of themes and ideas. It would be more appropriate to think of the anime and manga industry as equivalent to the Hollywood movie industry both in their breadth of genres and potential for individual creative style and direction.

There have always been various media to tell both old and new stories, including film, radio, novels, and more. For Japan, it appears that animation, comics, and graphic novels have captured the imaginative quest for escape, understanding, and entertainment at this point. The popularity of this medium for sheer storytelling power can be seen in the statistics with a steady ‘rise in the number of manga books and magazines published annually, from 1 billion 1980 to 2.27 billion in 1994,’ (Kondo, 1995, p. 3) which lends an element of truth to the often quoted fact that ‘Japan now uses more paper for its comics than it does for its toilet paper’ (Schodt, 1983, p. 14). So, how did this popularity of comics and animation occur? What changes for the future are in store with increased international interest? How does the productive process of anime and manga that exists within the social, political and historical systems of Japan affect the ability of a Western audience to identify with anime and manga characters and narrative and stylistic forms?

Indeed, how much of my own relationship with the image in manga and anime is based on a desire to escape into the exotic world of another popular culture without having to experience the social hardships and constraints that exist within that society? Is it the ultimate luxury of the voyeur to indulge in this form of sanctioned, sympathetic (mis)understanding? These questions pose a problem, revealing the anxiety that exists within the pleasures I find in anime/manga. These questions threaten to coagulate my inquiry into an undesirable relativism of cross-cultural ignorance. These unanswered questions form an uneasy backdrop to the conventional history of anime and manga that follows. The point is that definitive and totalising claims cannot be made of the emerging and dynamic medium of anime and manga. However, a possible line of inquiry that may illuminate this dense, inquisitive section is the issue of language as it relates to avoiding the Japanese original and understanding the subtitled or dubbed Western version.

The use of language within anime English dubs or maintaining the original Japanese spoken language with English subtitles is a constant source of debate among fans, revealing much about the marketing strategy of Western companies towards anime, as well as a fundamental shift in how an audience is perceived to relate to a text. A knowledge of the Japanese language is possibly the most significant difficulty in understanding amine and manga. As Adams & Hill Jr. (1991) state in their study of Japanese comics, ‘Japanese is a language characterised by indeterminateness’ (p. 102), made even more complex by the emphasis on slang and regional differences used in some anime and manga, such as the linguistic differences between rural and urban Japanese in the anime I can hear the sea (ocean) produced by Studio Ghibli. These make subtitling a nightmare of uncertainty and approximation, placing many Western fans at the mercy of dubious fan subs or the alternative of garish English dubs. The challenges of translation became clearer to me when I subscribed to the Video Girl Ai translation project on the internet, one of the many fan-initiated translation efforts currently being sweated over, where fans attempt to translate their favourite manga or anime and, in this case, set up a community centred around this exhausting task. Numerous flame wars erupt between these fans as they constantly revise translations to capture the flavour of the original text and honour the author’s intentions. In Rumiko Takahashi’s works, such as Urusei Yatsura [Those Obnoxious Aliens], Ranma 1/2, and Maison Ikkoku, readers encounter numerous translation difficulties due to puns in Japanese names and slang, as well as cultural references that are difficult to appreciate. As Takahashi (Princess of the Manga, 1989) said of the popularity of her work in the West:

“If it’s really true, then I’m truly happy. But I must also confess as to being rather puzzled as to why my work should be so well received. It’s my intention to be putting in a lot of Japanese references, Japanese lifestyle and feelings … even concepts such as a subtle awareness of the four seasons. I really have to wonder if foreign readers can understand all this, and if so, how?”

How do foreign readers attempt to understand this? Are there, in a Jungian (1964) sense, ‘universal themes’ and archetypal images played out in Takahashi’s stories that transgress language and cultural particulars? Or is the attraction in the experience of exploring an area that is both familiar to us and at the same time noticeably different from and ‘other’ to anything popular culture can provide in the West?

To discuss Japanese anime and manga is to understand areas of difference and ‘otherness’ that threaten to descend into notions of ‘us’ as Westerners versus ‘the other’ of the Orient with all the associative themes of culture, race, nationalism, the exotic, exploited past of colonial history and the cultural consumption of ‘otherness’ in non-Western images and ideas. Under the influence of post-colonial authors such as Edward W. Said I am aware of the tense positioning I am creating between myself as a white Australian male and my study of a popular form of Japanese culture. I deliberately use the clumsy term ‘white Australian male’ to raise the issue of race and gender as it relates to my relationship with the text. Raising these issues begs the questions, should these terms be important? Is it even productive to attempt to frame anime and manga in such a reductive environment? How do these terms fit into a multicultural society of Australia that attempts to praise diversity whilst never quite wanting to deal with the dominant Anglo myths that still cling to my perceptions of Japan? Consider, for instance, the recent advertising and general media coverage given to the 50th anniversary of the Victory in the Pacific in the Second World War, with all its notions of a victory for democracy and a dominant culture still resting, if somewhat frayed, in the ideals of a white British colonial empire.

Contemplating these questions emphasises the importance of appreciating the cultural, historical, social, and political backgrounds, as well as a knowledge of (or lack of) the Japanese language, that influence both the production of, and my understanding of, comics and animation. Kinko Ito (1994) emphasises a similar point with their call for a methodology resting on a visual sociology and content analysis of manga as “a way to systematically organise and summarise both manifest and latent content of communication.” (Light & Keller, as cited in Ito, 1994, p. 83).

The one issue that brings these questions to the fore is identity, both at a national and global level, with notions of East/West, Japan/Australia, and a more local notion of identity at an individual level, examining fan culture and individual reader/viewer responses. To achieve this, we need to explore new ways of understanding how anime and manga function, as they present unique possibilities that challenge and dismantle traditional binaries and perceptions of East/West, Male/Female, civilised/primitive, and us/other.

1.5 The Early History of Japanese Manga and Anime {#section-1-5}

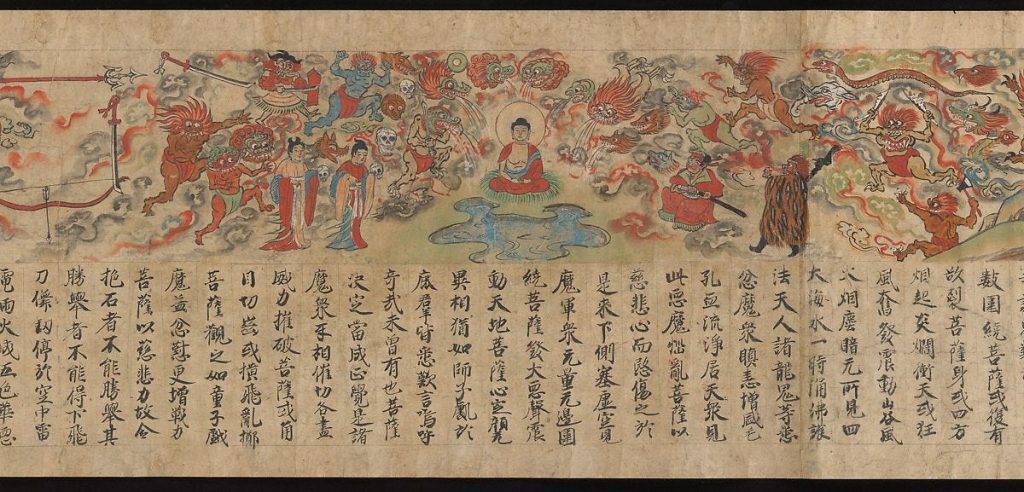

Leo Loveday and Satomi Chiba (1986) are amongst the many authors who have traced the historical origins of manga as far back as the picture scrolls of the 9th century. This era is widely recognised as an important time of development in Japanese art. Some mythopoeic critics (Campbell, 1962) have referred explicitly to these scrolls and their uniqueness. As Professor Langdon Warner (1962) points out, ‘…almost suddenly, and certainly without debt to foreign schools of painting, the Japanese were producing long horizontal scrolls of such narrative as the world had never seen’ (p. 488). Warner (1962) compares the Japanese scrolls to those existing in China and India, commenting that

‘… the Japanese showed peopled narratives beyond compare … The main difference is that the Chinese were largely interested in matters of philosophy, while the Japanese emphasised Man and what happened in the material world at a particular time’ (p. 488).

The themes of these scrolls (known as emaki-mono) ranged from epics, novels, and folk tales to religious themes and were drawn in a style that ranged from simple, clean lines to complex, colourful scenes inlaid with gold flakes (Loveday & Chiba, 1986, p. 162).

Loveday and Chiba (1968) go on to note that the

‘The most famous picture-scroll which is often cited as the “first” Japanese comic is Chojugiga (Frolicking Birds and Animals) which in a Walt Disney-like style has monkeys, rabbits and frogs impersonating the actions of human beings in one part and the antics of fantastic beasts such as dragons and unicorns in another. It dates back to the 11th century.’ (p. 170)

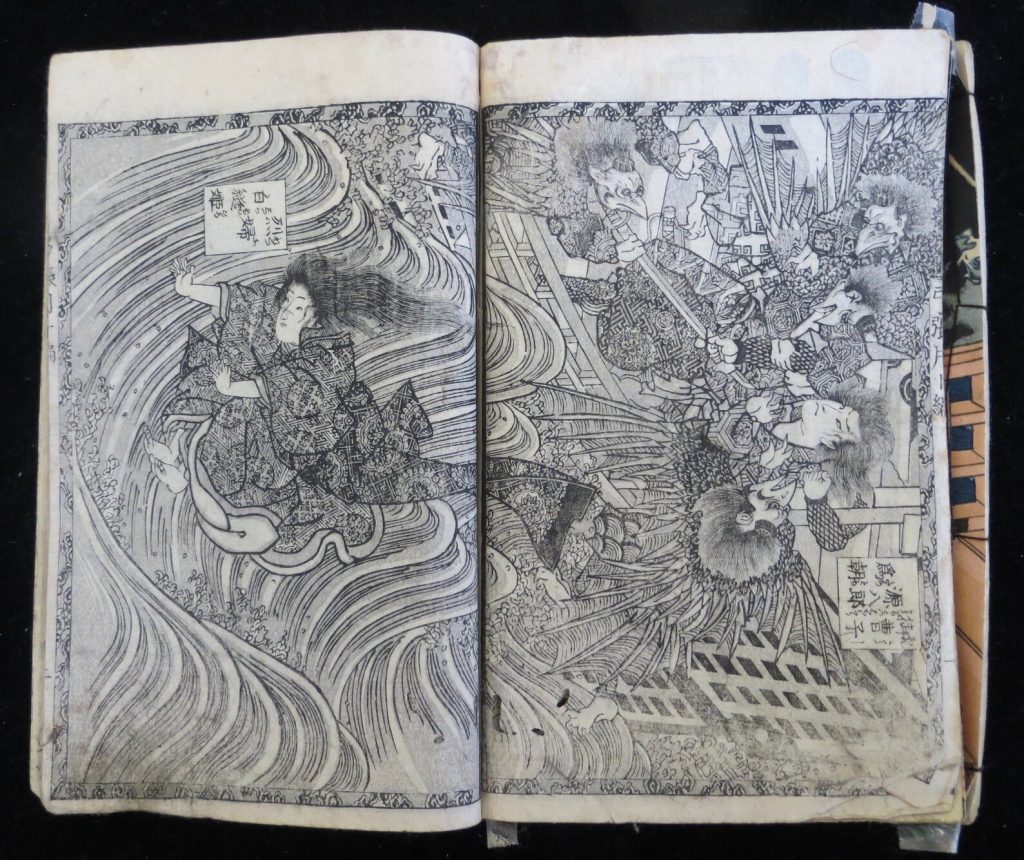

Frederik Schodt (1983, pp. 28–68) further developed claims, noticing that these scrolls were almost ‘animated’ as they were drawn on a long piece of paper and rolled along to read.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, woodblock printing became a popular and dominant art platform. Not only was this technology used to provide greater access to traditional folk tales and legends to children, the illiterate, and those ignorant of Japan’s classic culture, but it also developed a growing popularity amongst adults. By the 18th century, a sophisticated political literature (Kusazoshi) had developed. This development is even more interesting if one considers the similar development of manga in Japan, which initially began as material only targeted at children but quickly became popular amongst adults. See Loveday & Chiba’s (1986) discussion on aspects of the development of a visual culture with respect to comics: Japan.

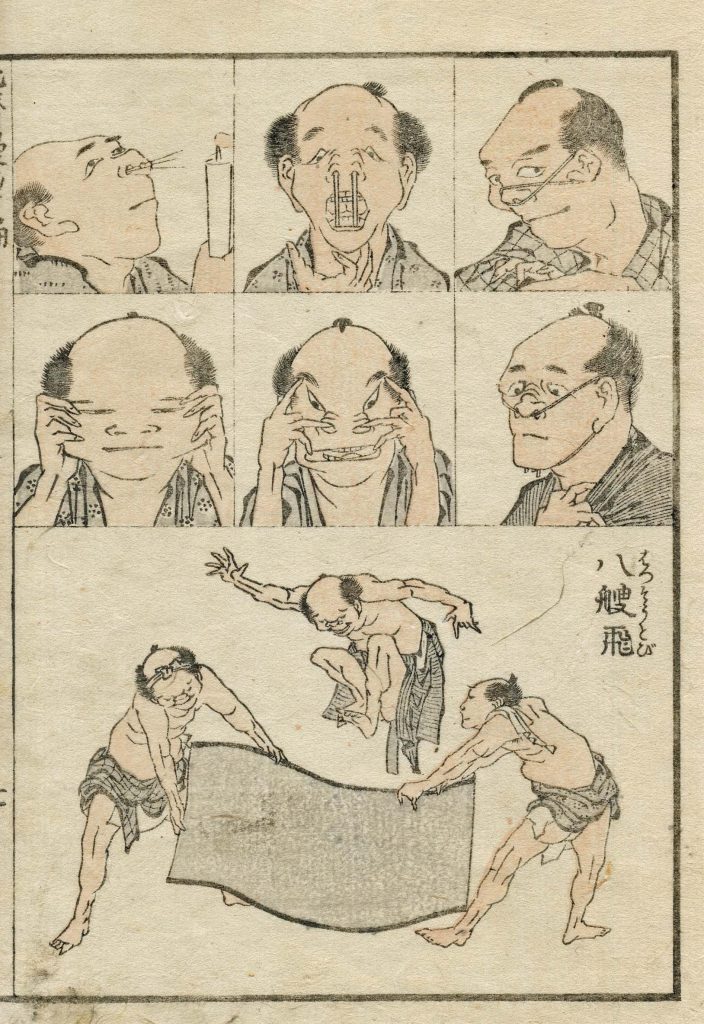

Stylistically, these political commentaries consisted of pictures with text appearing next to them. Hokusai (1769-1849) emerged as the central figure of this time, developing a striking and effective line-drawing technique that has influenced the style of modern comic artists (Loveday & Chiba, 1986, p. 162). Haden-Guest (1995) also see a strong connection between the style of the 18th and 19th-century woodblock artists and the art of the modernist period. The term manga was first coined during this period, suiting the irresponsible pictures of Hokusai’s imaginative and weird drawings so appropriately.

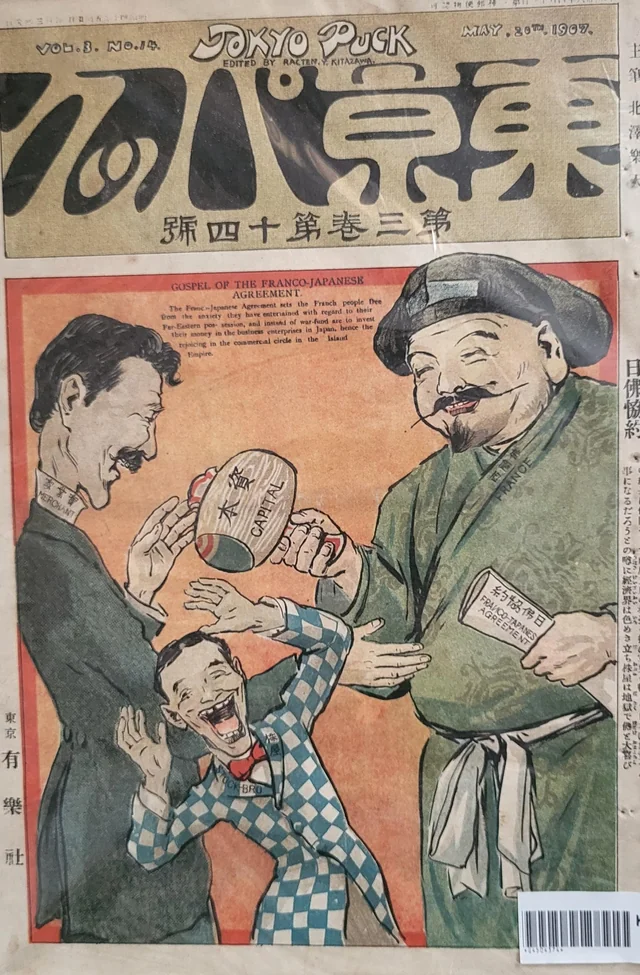

During the late 19th century, with the introduction of European satirical caricatures and comic strips for expat Westerners in Japan, we see the development of cartoons along more familiar Western lines. Japan Punch, published in 1861, marked the first significant western-style publication, leading to the establishment of daily newspapers during the Meiji Restoration. From 1868, the appearance of local comics and caricatures increased along with the employment of Japanese comic artists. The first Japanese satirical magazine devoted to cartoons, Tokyo Puck, appeared in 1906. Japanese artists also became increasingly influenced by Western artists, such as the 19th-century Western satirical graphic art and political and social caricatures, and the cartoons imported from the United States, such as Felix the Cat, Betty Boop and Popeye. However, from the 1930s until the end of World War II, the Japanese government increasingly used these publications in fascist propaganda (Schodt, 1983, pp. 55-60).

Often overlooked during this time was the beginning of the Japanese animation industry, which screened its first celluloid Japanese animated film in 1930. Before this, Japanese animators employed a paper/origami style that produced complicated patterns through a silhouette effect shot in a silent black-and-white film (Ono, 1995). From the 1930s onwards, animation, as a form of entertainment, began to be seen as an educational tool, especially during the war years. Despite this, the war years were not productive for animation and comics. The paper shortages reduced comic production, Japan banned U.S. animation and comics, and few people attended the cinema. After the war, manga and anime artists saw improvements as demand rapidly increased. The Japanese writer and critic Kosei Ono (1995) believes this may be due to parents wishing to provide more for their children than they had during the war.

The most popular artist at the time was Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka, referred to as the grandfather of Japanese manga and Japan’s Walt Disney, has been seen by many as the single most important factor in shaping Japan’s post-war manga culture (Temple of Manga, 1995). The Temple of Manga (1995) piece goes on to mention a tribute for Tezuka on the day after his death on February 10 1989, in Japan’s Asahi newspaper, which reads:

“Foreign visitors to Japan often find it difficult to understand why Japanese people like comics so much. For example, they often find it odd to see grown men and women engrossed in weekly comic magazines on the trains during commuter hours. One explanation for the popularity of comics in Japan, however, is that Japan had Osamu Tezuka, whereas other nations did not. Without Dr Tezuka, the postwar explosion in comics in Japan would not have been conceivable.” (p.26)

In the West, we mainly know of Tezuka through the popular children’s cartoons Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion. The current controversy surrounds this particular anime series, as many have noticed direct similarities to the big-budget Disney animated movie The Lion King. For those interested in this topic, I suggest Fred Pattern’s (1995) paper Simba versus Kimba: Parallels Between ‘Kimba, the White Lion’ and ‘The Lion King’, presented at Australia’s Second International Conference on Animation.

Tezuka’s presentation of the body with its hyper-cute, childlike features and the dense, involved plot that often contained spiritual and humanistic overtones set the pace for nearly all that was to follow. As Haden-Guest (1995) remarked:

“Look at Japanese anime, from bubblegum operas through to the darkest fantasies of destruction and weird sex, and everywhere you find the Tezuka touch, which is to say a merging of Yankee cuteness with astounding graphic sophistication, and both used to advance turbulently lapel-grabbing narratives” (p. 45).

Figure 2. The kawaii cyborg body. Gally (Eng. Alita) from Gunnm (Eng. Battle Angel Alita) (Yukito Kishiro, Eng. trans. 1994).

Cuteness, or kawaii, as it is termed in Japan, threatened to become a dominant aesthetic within manga and anime. Bodies became dominated by curves and circles, round and lithe little figures with eyes large enough to consume any viewer’s gaze. Japanese manga artists took to extremes the cute animal figures of Disney and the childish proportions of the Western Kewpie doll to revolutionise the body’s appearance in children’s entertainment.

For a fascinating look at the influence of European and American notions of cuteness on Japanese anime and manga, see Philip Brophy’s Ocular excess – a semiotic morphology of cartoon eyes in Kaboom: Explosive Animation from America and Japan Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 1994. Also, Pauline Moore’s Cuteness (Kawaii) in Japanese Animation: When Velvet Gloves Meet Iron Fists. Paper presented at Australia’s Second International Conference on Animation. Japan Cultural Centre, Sydney, March 3, & Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, March 4-5. 1995. She presents a fascinating look at the notion of infantile narcissism as it relates to the Japanese fixation on cuteness, the pre-adolescent teenage female body, the exploitation and violation of this body through marketing, and the conflict that the cute body encounters with the violent environment it so often lives in.

Fans have developed special terms to describe these characterisations, including ‘CB’ (Child Body), which refers to a character with a large head and the chubby body of a child, often used as a prefix, such as CB Astro Boy. ‘SD’ (Super Deformed) is often a parody technique that takes existing characters that are depicted realistically and squashes them into deformed midgets. Often these are incorporated within ‘realistic’ manga and anime to provide lampoon comedy, as in the manga Appleseed, or to parody the explanation of the ‘moral of the story’ or a complex and technical term, used effectively in the series Tenchi-Muyo. Often, these work to subvert or send up the heavy-handedness of issues.

Fans also actively use general Japanese terms, such as the suffix -chan, which means ‘darling or little one.’ People usually reserve this term of affection for small animals, children, romantic partners, or young female friends. Terms such as chan or chibi have been used in anime in the eighties to describe ‘squashed ‘versions of characters with enlarged heads and infantile bodies’ (McCarthy, 1993, pp. 6-7). The possible reason for this form and style could be an extension of the Japanese fascination with ‘doll women’ (Buruma, 1984, p. 67). These women train to control their motions in stilted, mechanical ways and speak in a high pitch, predominantly working as female elevator operators.

Phillip Brophy’s (1994) article Ocular excess – a semiotic morphology of cartoon eyes suggests that the attraction of the cute body in post-war Japan may be related to the traumatic experiences Japan experienced at the end of World War Two. As Brophy (1994) suggests, ‘… “cute” signified an idealised social world in which people, animals and things were infinitely happy and kind to each other’ (p. 48). However, as Brophy argues, in the Japanese context, the eyes of these cute bodies are kept violently open to the violence of Japan’s post-apocalyptic culture. Brophy suggests that the Japanese have created a unique spin on the notion of cute as defined in the West:

‘I would argue that the Japanese have in a confounding way appeared to embrace this particular Americanised therapeutically-designed version of Euro-cute; that they have been attracted to the hyper-iconic status of these grotesque figures which ‘cry out’ in sad-eyed silence; and that the Japanese have been able to imbue these postwar signs with a mystical resonance which remembers the past precisely by appropriating images designed to aid in forgetting it.’ (p. 49)

1.6 The Dance and Dream of Images

During the 1960s, two significant developments occurred within manga: the appearance of comics marketed towards young girls called shojo manga and the arrival of the gekiga (dramatic pictures) genre. Before the Second World War, the market mainly catered for boys with the dominant genre known as shonen manga (young boys’ comics). It was not until after the war that the market began to diversify and cater to both sexes, adults, children, and teens. However, these categories are not fixed and stable. Many adult women will read shojo manga, and many men will continue with shonen titles from their boyhood, as well as the cross-readership between titles and genres by men and women, boys and girls.

We can make some general observations about shojo and shonen manga. Shonen manga is the broadest of the categories, and many of the themes covered in anime and manga can be said to cater for this audience. Typically, shonen manga concentrate on sports or action fields.

Shojo manga caters to the interests of girls and young women. While the shojo genre has faced conservative criticism for its reliance on ‘simplistic romance plots’, it also possesses the potential for some of the most artistic and literary achievements in manga and anime. For example, the Mania Muki style concentrates on the extreme occult and science-fiction genre (Page, 1994, pp. 107-109). During the 1980s, shojo manga and anime evolved into sophisticated romance, occult, and dramatic titles. Shojo manga had been developing since the 1970s with the genre’s first major female artist, Riyoko Ikeda, whose The Rose of Versailles detailed a fictional account of Oscar, a noblewoman forced to live disguised as a man in the court of Marie Antoinette, which went on to become a best seller.

Currently, the best-known artist in this field is Rumiko Takahashi, known as ‘the manga princess’ by fans. Her best-known titles include the misadventures of an alien princess on Earth in Urusei Yatsura (Those Obnoxious Aliens); a struggling school student swatting for exams in Maison Ikkoku, and the gender/animal bender Ranma 1/2, where the main characters become transformed into male, female or Panda Bears. Shojo manga and anime involve several female artists working in the most radical and controversial areas of manga and anime. Shungiku Uchida’s adult manga have been described by one critic as tough on controversial topics such as sex between unmarried couples and extra-marital affairs, in the process blatantly going against the unquestioned moral order that Japanese women should be untainted and demure. Her openness to traditionally taboo issues explains why the Japanese media have labelled her “scandalous” (Matsubara, 1994, p. 70).

The bishonen subgenre showcases a “pretty boys” animation style, featuring male characters with delicate, thin features, wide eyes, and a highly feminine appearance. Another mini-genre is Shonen Ai, which focuses on romantic stories between men. Recent discussions in the rec.arts.anime newsgroup, particularly under the title “Homosexuality in Anime,” have explored the prevalence of sexually ambiguous characters in anime. For example, these discussions often cite the character Subaru from the anime “Tokyo Babylon” by Clamp. Strong storyline narrative dominates the work of the CLAMP artists, a group of four women whose works include the occult thriller Tokyo Babylon, Campus Guard Duklyon, and Rayearth. Their stories always have an unexpected twist at the end. The four alien girls in Rayearth are summoned to Earth to defend their host, only to discover their true mission is to kill him (Kondo, 1995, p. 4). Other controversial shojo artists include Minami Ozaki, known for Bizarre Love 1989 and Bronze, whose work offers an intensity of style and unconventional use of symbols, such as the depiction of swastika earrings worn by bishonen gay men (Page, 1994, p. 108). Natsumi Itsuki’s and Yasuko Aoike’s gay and lesbian love stories are equally open and brazen about their subject matter.

In addition to these general ‘gender and age’ categories, several specific genres are important in understanding the social saturation manga and anime have achieved in Japan. Manga and anime are far more than the simple hero adventures that dominate most, if not all, of the comics in mainstream American and British stores.

I realise this is a broad generalisation and does not take into account the important underground graphic artists of the 60s and 70s in America such as Ralph Bakshi and Robert Crumb, the comics in MAD magazine, the Warner Bros. cartoons from the 1930s through to the late 1950s, and the current unconventional cartoons such as John Kricfalusi’s Ren and Stimpy and Mike Judge’s Beavis and Butt-Head. However, these are only notable exceptions in a field still strongly dominated by notions that animation and comics are only for children and teenagers, restrictions on depicting violence or death during cartoons, and the aesthetic of the politically conservative Disney stable of animation, which lacks the diversity and radical edge of much anime and manga. For a further discussion of this, see Chris Staros (1995, pp. 18-22) and the interviews with American artists in Kaboom (1994).

The legitimate status of manga and anime as valid forms of art in Japan elevates their cultural significance, fueled by the industry’s diversity and dynamism, attributes that Anglo readers may find more challenging to appreciate fully. To generalise, Europe is the only other area that has placed animation and graphic novels on a valid artistic level, which directly conflicts with the approach taken by many in the US and the UK.

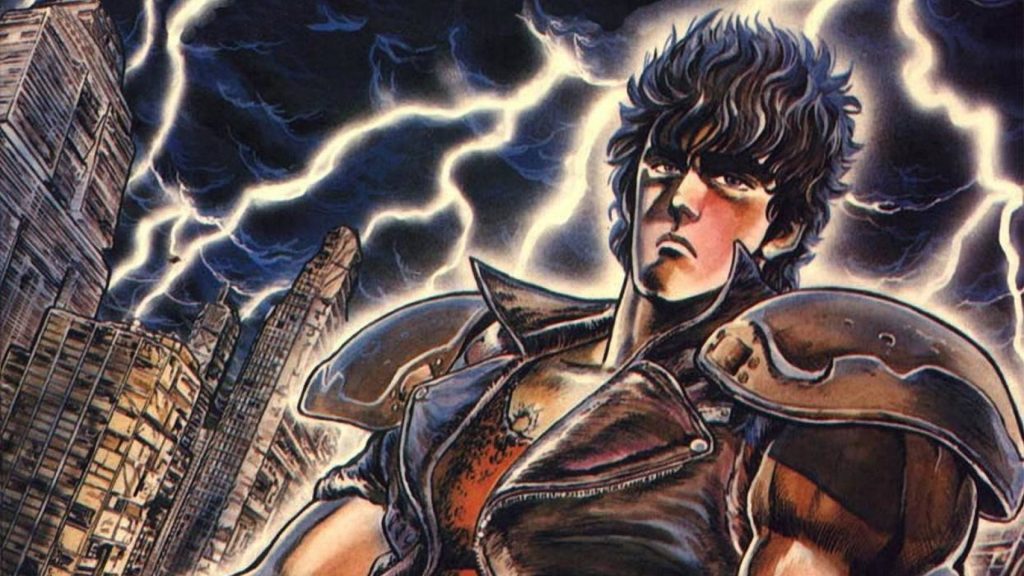

One of Japan’s first important styles to emerge during the 1960s was gekiga or ‘drama-pictures’. This style directly challenged the ‘Tezuka school’ of cute characters with big, round eyes. Geikiga artists favoured a more realistic rendering, which suited historical works. However, they were equally effective in depicting modern settings, concentrating on political or social themes. Cyberpunk anime like the grim, Blade Runner-esque AD Police have also utilised these themes. This style had a hard-edged ‘reality’ that, combined with the pure fantastic, would push the limits of how animation and graphic novels could depict ‘life’. For instance, the controversial anime Urotsukidoji redefined the depictions of sex and violence in a dense, apocalyptic and spiritual storyline. The geikiga style was also adapted to Samurai and sports stories, which became the two biggest genres during this period. Working on themes of honour and endurance, these genres, especially samurai, contained philosophical elements and captured the harsh tone of gekiga realism with adventure/action themes. The early 1960s were a dramatic time for Japanese society. Japan hosted the Olympic Games in 1964; the 1960s were the decade in which Japan’s economy began to flourish. These events caused dramatic changes in Japanese society and directly affected the manga and anime industry. The buildup towards the Olympic Games caused increased building development, business opportunities, and cultural and social publicity involving increased interaction with the world community. This push towards rapid post-war development and economic boom would be a continuing theme in many anime and manga stories, such as the developing “Neo-Tokyo” in Akira; indeed, the notion of ‘new birth’ and cyclic patterns of destruction and renewal form a dominant theme in many post-apocalyptic stories such as Fist of the North Star and Urotsukidoji.

The economic boom resulted from increased disposable income; people were more than willing to spend on manga and anime products. The commercial viability of comics and animation made them cheap and accessible. A typical manga would be about 1 to 2 inches thick and about 150-200 pages long, about the same size as a telephone book. Comics and animation rivalled all other forms of popular culture. As Kosei Ono remarked at the Life of Illusion Conference in Sydney, 1995, when he left Japan to attend the conference, the top two films at that moment were a Japanese animated movie and a Godzilla film. The acceptability and popularity of anime and manga have placed them within a privileged position in Japanese culture, going far beyond their popular origins and spreading outwards into politics, advertising, and education. It is an act of communication that resonates with a unique ability to capture areas of the fantastic, social, and political. As Anthony Haden-Guest (1995) suggests, of the power of the animated fantasy over live-action cinema:

With Akira and Legend of the Overfiend, as with most of this genre of anime, you are suddenly aware that animation has powers not given to live-action movies, regardless of the money spent on special effects. An animator can take you inside an atom, can control a flame, analyse destruction, hold the universe in the hollow of his or her hand. It’s beyond burning buildings and exploding cars. The animator can recreate and exert some psychological control over one of the world’s worst nightmares. (p. 47)

The ability of artists working within the manga and anime form to express complex and sophisticated story lines and offer escapist fantasy is at the heart of their popularity. Manga and anime have assumed the position of the novels and live-action movies of the West: they have become the dominant and most influential popular art form in Japan, offering a fertile ground of sounds, images, themes and ideas that rival, if not surpass, the fantasy offered by mainstream live-action cinema. As Hisashi Kondo (1995, p. 8) comments,

Some observers say that the manga is about to replace other genres, especially the novel, in performing the storytelling function. Others maintain that young writers are beginning to write novels in a ‘manga style.’

How is it possible for animation and graphic novels to assume such a status in Japan? Some, such as Masaru Akutsu of Kodansha’s International Division, a distributor of manga and anime, say that this is due to the accessibility of manga in Japan and the creative possibilities offered within manga and anime:

I still believe the reason manga developed to such an extent in Japan is their low cost. In the early days, manga could be produced far more easily than movies, then the king of entertainment in Japan. So, if a cartoonist had talent, he could easily express himself in any way he wished. … This ease of expression gave manga a considerable degree of freedom, enabling the creators to experiment with all modes of expression. (in Kondo, 1995, p. 9)

One significant event that redefined the anime market was the explosion of OVAs (Original Video Animations). This category refers to anime released directly to the market through VHS rather than first broadcast on television or in the cinema. The most significant advantage of this approach was, as Andrew Leonard describes, that:

Anime creators benefited, especially those working within the tight production schedules imposed by television. Not only did a longer production cycle lead to improved production values, but bypassing television restrictions on content allowed animators to indulge themselves in creating scenes filled with graphic violence or explicit sexual content (Leonard, 1995, p. 182).

Animators gained the freedom to produce a wider variety of titles and explore more risqué subject matter, as they no longer faced the tight content control of television regulations, sponsor pressure, or the costly and labour-intensive process of creating animated movies. Some hentai (perverted) titles released in the West include Manga Corps Ujin Brand, Angel of Darkness, and Go Nagi’s The Adventures of Kekkou Kamen, released by East2West Films. Notably, the last two titles portray a high school that has become the location for sadistic and evil acts by the teaching staff upon the young, innocent students. Anime artist Takashi Oshiguchi suggests that this freedom created an environment of experimentation that increased the stylisation of speed and dynamic movement offered by OVAs:

With OVAs, the authors and artists can concentrate on what they want to do. They have more artistic freedom and more time to produce. Such conditions might influence this increase in sophisticated movement in animation. (Oshiguchi Interview: Philip talks to Takashi Oshiguchi in Kaboom, 1994, p. 154)

By the mid-1980s, animators produced more content than ever, with many exploring extreme and provocative themes. This period saw a significant surge in the hentai genre, often referred to as “juicy manga,” which primarily consisted of soft-core pornography. Despite this development, publishers continued to release traditional titles in science fiction, fantasy, detective stories, the occult, and romance. However, the growth of the hentai category became the most significant trend during the 1980s and early 1990s, challenging the government’s liberal attitude toward anime and manga.

The depiction of sex in manga and anime has been an area often criticised by the Western press; however, this reporting is often exaggerated and rife with cultural assumptions. The Japanese have a long history of erotic drawings, and much of this work exhibits a sensuous and culturally open-minded attitude towards sex that differs from the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ attitude of many Westerners. As Helen McCarthy (1993, p. 48) writes:

“In Japan, people freely embrace a wide range of sexual preferences and fantasies, thanks to a long tradition of liberal thought that cultivates an atmosphere where anything is permissible in the privacy of one’s own imagination. Anime provides a wide range of choices, from the mildly erotic to the frankly pornographic.”

One author estimated that in 1992, a quarter of all manga contained sexual content (Sabin, 1993, p. 208). However, most of this is not explicit, with laws against the depiction of genitals, the sexual act and pubic hair, which are often digitised or blacked out. As Roger Sabin (1993, p. 285) points out on the legal issue of pornography in Japanese popular culture:

“The main legal barrier to this kind of subject matter (explicit sexual references) is Article 175 of the Penal Code. There is one loophole, however: children’s genitals are allowed to be shown. This has led to a thriving industry in child pornography, or ‘Lolita comics’ as they are known. In the 1990s, a protest lobby has emerged, and there is now a possibility of new laws being passed.”

Generally, there appears to be a far broader acceptance of nudity and sexuality in Japan than in the U.S., Britain, or Australia (Stockbridge, 1994, pp. 86-92). As for the reasoning behind this cultural difference and the impact it has on the issue of censorship, Masuo Ueda of the Japanese Sunrise company claims that,

“We have no censor groups. But there aren’t real censorship bodies here in Japan, no official organisation to check violent scenes or sexual scenes. We therefore have to rely on government policy relating to broadcast. And on the ethics of the Japanese people, because if we hide violent scenes, children have to get used to unnatural depictions of things. For example, we have much sex and violence in society. We can hide it but this is not natural; this is not reality. So we Japanese people have thought it better for a long time not to hide anything. From a business view, it’s also better for us to do more stimulating scenes, and those scenes have been supported by children.” (Ueda Interview: Philip Brophy talks to Masuo Ueda in Kaboom, 1994, p. 150)

Although this betrays an attitude of ‘the readers want it’ which would require further research and study to explain, it does display a unique attitude towards an unnatural depiction of things, which is of refreshing contrast to the attitude of many western children’s programmers, with no or little incorporation of violence and its consequences of death and pain. Japanese children’s animation has always provided a contrast to the usual Western fare, with imported shows into Australia like Robotech offering a vast difference to the stock Western cartoons, as one fan reminisces

“‘Robotech was always the talk of the classroom,’ says Mike Tatsugawa, 24, … ‘It didn’t have a kiddie storyline, it covered relationships, it had drinking and violence; it was like an animated soap opera. I remember Robotech was at 4:30, the Smurfs at 3:30. The dichotomy was really frightening’.” (Yang, 1992, p. 56)

Another reason behind Japan’s liberal approach to censorship could be that ‘Japanese officialdom sees fictional violence, sexual or otherwise, as a safety valve’ (Sabin, 1993, p. 208). In order to maintain social order and conformity, Sabin suggests the government tacitly condones vicarious violence through manga and anime. As Ian Buruma (1984, p. 224) in his study of Japanese popular culture observes: ‘Encouraging people to act out their violent impulses in fantasy, while suppressing them in real life, is an effective way of preserving order.’ Although researchers have yet to establish a direct causal link between the violence depicted in anime and manga and aggressive behaviour, they often rely heavily on personal opinions and speculation when discussing the boundaries between reality and fantasy. The distinction between these two categories is not always clear-cut. However, this does not imply that opposing the media’s portrayal of violence and sexual content is ineffective; quite the contrary.

In 1990, activists launched the first major protest against sexual depictions in comics, uniting an intriguing alliance of anti-pornography feminists and right-wing conservatives. Their collaboration primarily revolves around concerns about the portrayal of women in mainstream media, which has shaped the evolving political landscape in Britain, the USA, and Australia. For a more detailed examination of the relationship between censorship and pornography, refer to Andrew Ross’s work (1989, pp. 171-208). For a comprehensive analysis of pornography in contemporary society, see Linda Williams’s book, “Hard Core,” published by Pandora in London in 1990.

The depiction of women in pornography is a highly political issue that revolves around media regulation and control (Nightingale & Turner, 1990, p. 291). As a result, scholars have written numerous academic articles, and the Japanese parliament has made significant policy shifts. In 1991, the Council of Ethics on Publications made a significant policy decision, which mandated that all seinen manga (adult comics) be marked with a red sticker indicating that they contain adult material. This decision had ethical and political ramifications, leading many publishers to choose not to publish manga requiring this red sticker. The Metropolitan Police Board in Tokyo went on to propose four steps that should be taken to improve local legislation towards the accessibility of some manga. These include:

- the designation of harmful material immediately following publication

- stipulation of a regulation that allows residents to inform the authority

- prohibition of the sale of harmful material by vending machines, and

- increasingly severe punishment for those convicted.

(Asahi Shimbum in Ito, 1994, pp. 92-93.)

Many academic articles have savaged Japanese popular culture, including those that strongly endorse the regulation and control of manga and anime, especially when it comes to audiences that are deemed vulnerable to violent and pornographic scenes, such as children. As Kinko Ito (1994, p. 92) argues:

As agents of socialisation, these comic magazines play a very important role in transmitting cultural values, beliefs, norms, and rules. Sexual behaviour, just like any other social behaviour, is not necessarily instinctive but socially patterned and socially learned. Thus, sexually explicit, adult material comic magazines that degrade women must be kept away from young readers who cannot read them critically; they may not be able to tell ‘fantasy’ from reality.